I’ll Fly Away: Solo Exhibition of Rosy Keyser

“I caught that look on the face of a listener which told me that the invisible wires had been connected, that something was being communicated which was over and above language, over and above personality, something magical which we recognize in dream and which makes the face of the sleeper relax and expand with a bloom such as we rarely see in waking life.”

Henry Miller, The Colossus of Maroussi

Shifting States

Since a young age, Rosy Keyser has lived between tranquil rural areas and busy metropolitan centers. She has found a habit of shifting in and out of these very different environments. What interests the artist is not only the differences between these surroundings nor choosing one situation over the other, but the process of transition and transformation. Her perceptiveness of varying states and the world around her is expressed through her creative practice.

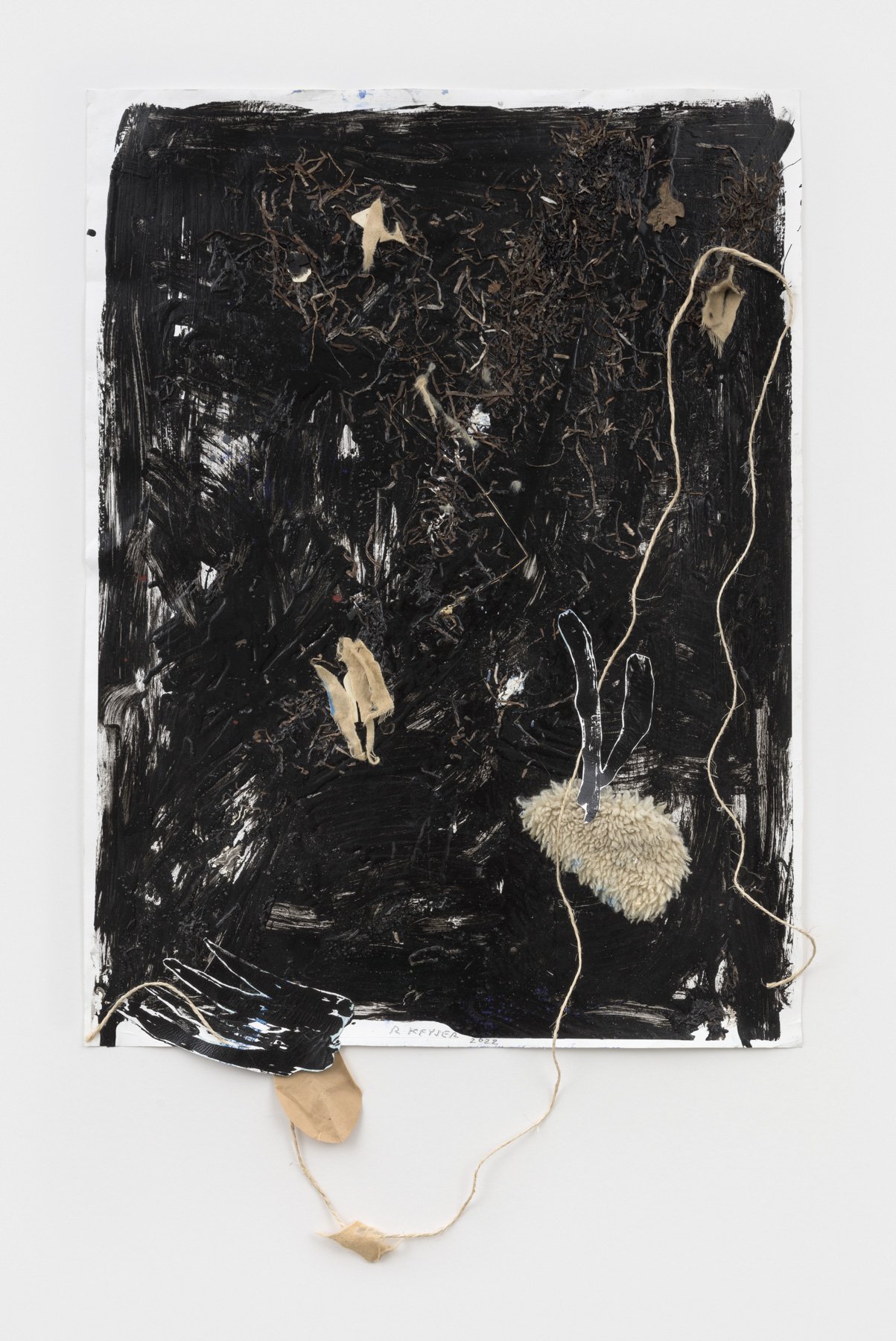

This consideration and energetic tension can be felt through her works. In one of her recent works, Medusa Elegy, paints of different colors spread across the background, while other materials such as seaweed or cut papers are orchestrated into a pensive abstract form that creates a contrast to the wildly spread colors.

Rosy Keyser is a native of Baltimore, Maryland. After a BFA at Cornell University, Keyser went on to graduate with a masters degree in Painting from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. The artist now lives in New York State, splitting her time between Brooklyn and Medusa.

Keyser is known as a painter who is never shy to tackle big or small challenges on the canvas. Those who are familiar with her past works and exhibitions would remember how diverse her materials and subjects are. Rosy Keyser does not only incorporate found materials or objects as a part of her artworks when the works invite, she lets them take on the role as a dynamic tool or compositional influencer. In some of her 2012 works, large pieces of scavenged corrugated steel are used, the time-honored and weather-beaten material becomes a unique rib cage and creates an unpredictable space when it hugs the canvas or stretcher, and sometimes the painting is even devoid of canvas. These works are both paintings and sculptures, and they would differ from the more gestural works with free and bursting brushstrokes in her other series such as Periscope, a swirling investigation into gravity and a curious way of asking how methods of observation influence how we see what we see. Sometimes her artworks revolve around a theme that inspires her at the moment, such as syncopated rhythms in Southern Music or structure in minimalist poetry and caligrammes (shaped poems).

For her first solo exhibition in Taipei with Nunu Fine Art, Keyser brings a series of new works that are not only demonstrative of her versatility and powerful grasp of her medium, but also offer a profound insight into her recent residency on the Danish island of Læsø. In this exhibition, Keyser brings 10 new mixed-media abstract paintings that she began on Læsø and subsequently completed in Brooklyn. The works encompass the artist’s extensive exploration and thoughts on human states of being, the inner spiritual connection to the outer world, and a deeper reality that goes beyond ideas and languages and may only be grasped through the spiritual senses. The work in this show reflects a state of ‘free-fall’ where the figure and the environment are pushed through a process which encourages an integrated “oneness”.

Generally speaking, Keyser’s vantage points and references are diverse and porous. At times they could seem unconventional and shocking, such as one of her past exhibitions titled “Hell Bitch” that features a dominating physical matrix (the first painting in a series) which generates a new and unrestrained group of paintings that constitute a “social contract”. Sometimes they are rather earthy and quotidian: advertising sign posters (for music festivals) that provide the essential cue. This exhibition title, “I’ll Fly Away”, an early 20th century spiritual hymn, also famously sung by Willie Nelson, brings the audience to Keyser’s interest in the playfully shifting states of nature through which things recalibrate, reorganize, restructure constantly. The title also suggests the artist’s search for transcendence beyond a static world.

Apparitions, Being and the Mind

When asked about her experience on Læsø and how it influenced her work there, Keyser describes how being alone afforded a subtle, multilayered, and reflective mental state. She believes this change of scene had stripped away the noise and distortion of a city and encouraged a more integrated and embodied experience.

As the artist settled into these new surroundings to create, she was struck by the profound conflict between longing and presence. Longing may be many things, ambient and vast or granular and sharp, like a tiny poison dart in the heart. In Keyser’s case, longing translated to yearning for intimacy, familiarity, and closeness to family. Presence, in this context meant a giving oneself fully to process in the interest of freedom and invention, no strings attached. Indeed, this whipsaw rodeo provides the friction that fuels creation.

In one of Keyser’s works, Læsø Jazz, the artist reflects upon her experience of encountering a small billboard on the roadside at night, partially hidden by a tree. In the painting, her imagination, in combination with desire and the rich potential of an incomplete set of compass points explode into an image of black with lines and dots in yellow. The painting is not a mere representation of the encounter at night, but a creative reflection on the embodied experience of maintaining wonder and allowing things to flow freely in and out of her work.

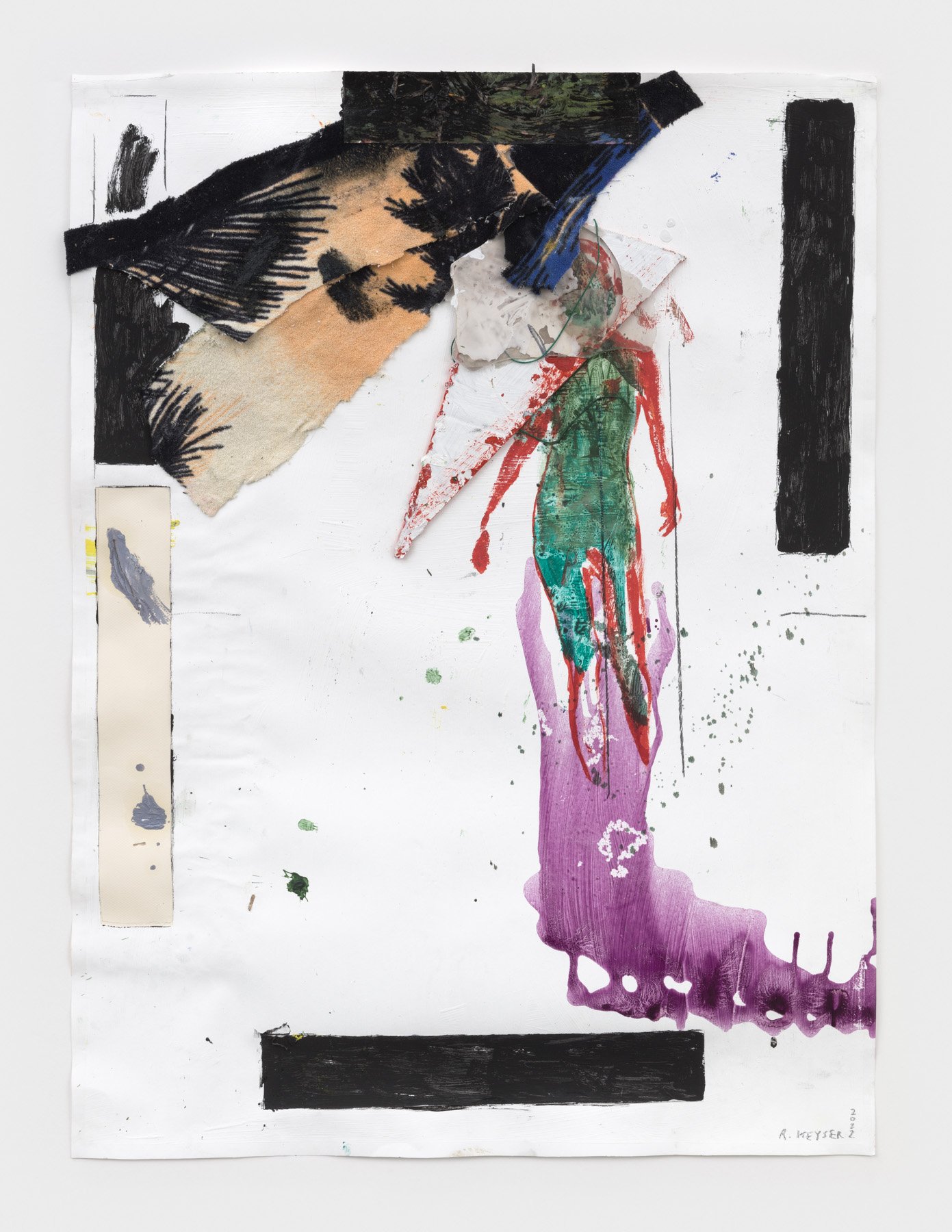

Keyser also evokes her reflections on the dream state through the process of collage. This oneiric stage is what mediates the recognizable and more lucid realities with the hallucinatory and unrestrained imagination, allowing novel visual happenings. For example, in Madame Horseshoe and Madame Vapor, images of a hidden human figure are incorporated into the painted image. Their forms, combined with abstract composition, take on the quality of a dream, perhaps a hazy map which guides us towards the spiritual world.

The Limping Eye

Through an artwork, we see the world through the artist’s eye. What is this vision like? Very often, this question is not asked. We assume that the painter has a perfectly clear vision, be it over familiar places and peoples or embarked upon an adventure to discover the uncanny and strange, showing us a snapshot of the world through their eyes and work. Rosy Keyser brings the viewers back to the basics by asking this fundamental and challenging question.

Like Berlin-based Korean philosopher and cultural theorist Byung-Chul Han, Keyser also questions the meaning of beauty in this brave new digital age, where everything could be duplicated and embellished. For something that is unique, handmade, and equally serendipitous as a painting, it is also relevant to rethink its meaning in a contemporary context. According to Han, the act of seeing can be understood as an injuring act. The act of contemplating, constantly seeing, the allowance of vulnerability, then becomes a constant injury, establishing a relationship between the viewer and the painted surface, but it is also the price to pay to experience something of a “new truth,” a novel dilemma.

In one of Keyser’s new works in the exhibition, The Injured Eye, she tries to convey this idea and continues her exploration on this line of thought through her painting. The black deployed on the white paper occupies the upper right of the image- a large color stain that covers up a vague human figure, the blue running below. The painting reflects, perhaps, upon the act of looking as an injury during the process of striving to experience, instead of looking, something that goes beyond our epistemological lexicon.

This idea comes back to Rosy Keyser as she works on her latest paintings. A typical day on Læsø is quiet, owing to its remote location in the Baltic Sea, off the windswept coast of Northeast Jutland. Keyser had known Læsø some years ago as visitor and returned this time as the first international artist in the Læsø artist-in-residence program housed in the former studio of the late painter Per Kirkeby. This prolonged stay has afforded her the time and space to read, swim, listen to birds, and take long walks from farmland to the forest to beach. The walks at dusk, prove most moving and inspiring, providing a world of sensory data and questions regarding perception. This crepuscular time between daylight and the dark night is one of shifting states, full of possibilities as it is the hardest time of the day to see objects clearly and confirm the body’s place in space. As the light subdues, the surrounding landscape seems to gain a granular quality. Bats may be seen flying in the sky, like scenes of an old film on negative that we look back to with nostalgia. There is beauty in measuring time by light instead of numbers and freedom in letting go of our conditioned obsession with a focused image.

During her three months in Denmark, Keyser was able to connect with a new audience and a different set of artworks. She prepared lectures and presented her works: a process of organizing thoughts, editing, and articulating progress thus far. The painter also had the opportunity to visit museums in Denmark, Sweden, and Norway. While in Oslo, Keyser saw a series of works from 1930 that the Nordic painter Edvard Munch made while he was suffering from an eye injury, a hemorrhage within his right eye, which affected the clarity of his sight. Her encounter with these works inspired Keyser to further explore the idea of an injured eye and its relationship to fidelity and beauty. The works made in this compromised state are revealing. The condition of this injury can create a fog and cast the shadow of a spector which bewitches and destabilizes resulting in a vulnerability. This injury invites a new and strange intimacy with the viewer. Like the loosely meandering rope in Yamabushi’s Crumb Trail and the printed pattern from a camping mat on Remora’s Lust, the asymmetrical and very human interventions of mnemonic mapping in these works provide a bodily tactile experience. There is something mortally familiar in this imperfection, like a limp that reminds people of their humanity and fragile states of certainty.

Being in residence is like facing a mirror, the artist must face themselves and their practices on unfamiliar terrain. This uncomfortable but necessary exercise opens up new paths in thinking and creating. Connecting the dots together, Keyser’s newly found insights are thoroughly reflected in her new works.

In contrast to her previous works on canvas, the works exhibited in I’ll Fly Away are primarily paper-based works. According to Keyser, the porosity of paper offers a listening quality which is sensitive and highly responsive to both accumulation and consolidation. There is a paradox of sorts: In a work on paper there are fewer places for gesture to hide and because the exhibited works endeavor to animate the transitive, elastic, and adaptive qualities of form and relative relationships of scale, we see the whole voyage of a mark exposed more fully. For example, in Remora’s Lust, the artist introduces such unconventional materials as sawdust and camping mat into the image, forming a diverse surface of material qualities and scales. While Keyser admires the early 20th century collage experiments of the cubist era: works by Picasso of Braque, she maintains that collage now must go beyond juxtaposition and move towards collapse of edges and expanded space of shared attributes.

Among the works of collage on exhibition this time, Thunderstruck Ved Grøn (Dispersion Version) is a particular one. In this painting, Keyser combines slick transparent paper with paints on unprimed linen, allowing surfaces of different textures to join each other and form a composite object that oscillates between presence and longing (expressed as reflection here).

In addition to observing the subtle dance of light upon landscape on Læsø, Keyser implicated her body as a means to capturing studies of scale. The Sculptures by Kirkeby at Haabet (The Danish artist’s studio) occupy a grassy area known as the ”Test Field”. Keyser made studies of these older artworks by gently wrapping the sculptures with thin paper and making charcoal rubbings to accurately record their idiosyncrasies of surface and size. These drawings, completely “to-scale,” are then transferred to the canvas to generate an initial composition. These works become a communion between the artist and the locality, involving the body and the landscape. Through this visceral experience, the painting finds a way to speak to the landscape that is tethered to both practical and sensual experience. The subsequent painting, memorializing the formal qualities of an artwork elsewhere as well as the artist’s interaction with that sculpture is a forced study in questions of originality, inspiration, ephemerality, and attachment.

There and Back Again

Brooklyn: Returning to the studio she knows best, Keyser notices that the tension between longing and presence persists, though in new ways. She is wanting to protect the insights gained in her time of solitude and reflection while allowing new energy to run rampant. Keyser returns to canvases in various stages of completion in her studio and is struck with new ways to move forward. Certain directions become clear, promising solutions abound, but the wildness only tolerates only so much taming.

The idea of ecology, of our relationships in communion with others and our surroundings, natural and cultural, reminds the artist that everything is always changing. How do we, in mind, body, and spirit, fit into this world and identify anchoring points in a changing and complex network of connections and relationships? Keyser’s new works become both a milestone and evidence of her continuing exploration of painting’s potential. This adventure is not devoid of dangers and uneasiness, and the exercise of coming back to challenge the very matter of painting again and again makes it meaningful. Rosy Keyser does this with bravura and raw honesty, letting the experience evoke novelty in her and for the audience.

Artist